2015 Finalist Tim Hewson (UK) about implementation of his idea

Since reaching the 2015 Harry Otten prize final, the “Point Rainfall” idea of Tim Hewson and Florian Pappenberger has gone from strength to strength. The idea involves applying a new and innovative post-processing technique, to ensemble-based probabilistic weather forecasts for the world (that denote area-averages, for regions covering about 400 km2), to accurately predict rainfall at points, i.e. as measured by rain gauges.

ECMWF initially recruited a graduate trainee to work on this, from January 2016, and following considerable R&D work, examining the predictive value of different input variables, and a major effort to create code that runs in real-time on a supercomputer, the first operational point rainfall forecasts became available to ECMWF customers in April 2019. Initial feedback has been very positive, which mirrors the impressive verification scores. These global scores show that, relative to raw model output, the post-processed forecasts are not only much more reliable, in a statistical sense, but are also much better at discriminating occasions when extreme point totals are possible. Useful skill in this respect extends as much as 6 or 7 days into the future; for the raw model output it is barely 1 day. Thus, we can predict when there is a risk of flash floods much more accurately than hitherto.

To support expansion of the work, we have been involved in consortia bids for EU funding. These have delivered 650,000 Euros for ECMWF, and four scientists are now directly involved. Meanwhile the number of project spin-offs continues to grow. For example, a related open-source GUI tool for calibration, to benefit the wider meteorological community, has been developed. And we will also create a unique, daily, global point rainfall dataset, extending back to 1950, based on the ERA5 re-analysis. For more information on point rainfall forecasts, and related links, see here.

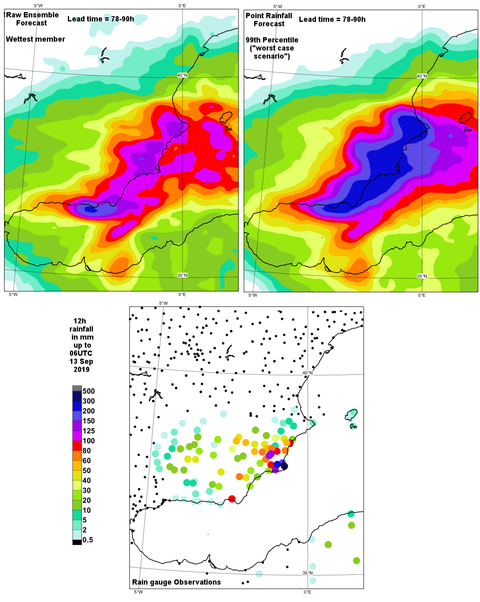

An operational point rainfall forecast from ECMWF for southeast Spain (above, right) compared with an equivalent 100th percentile field from the raw ECMWF ensemble (above, left) with verifying observations for the same 12-hour period (bottom). The “worst case scenario” shown on the right (strictly with a 1 in 100 chance of exceedance) matches better the most extreme totals measured, which lead to severe flash floods. The peak 12-hour total reported to ECMWF during this severe weather episode (which lasted 2-3 days, and which had widespread media coverage) was 314mm in La Manga (dark blue spot). (Click figure to enlarge)